- Home

- Tina Alexis Allen

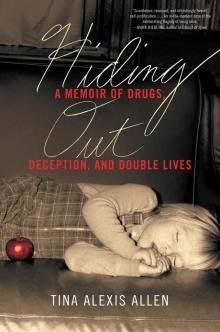

Hiding Out

Hiding Out Read online

Disclaimer

This is a work of nonfiction. The events and experiences I describe are all true and have been faithfully rendered as I have remembered them, to the best of my ability. I have changed the names of the members of my family and those closest to me in order to protect their privacy. Though conversations come from my keen recollection of them, they are not written to represent word-for-word accounts; rather, I’ve retold them in a way that reveals the meaning of what was said and the spirit of the moment.

Dedication

For everyone who hasn’t yet spoken up, written it out, or quietly embraced their story

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Disclaimer

Dedication

Prologue

1: Congregation

2: Blessings

3: Ascension

4: Revelation

5: Covenant

6: Chosen

7: Missions

8: Love

9: Condemnation

10: Mysteries

11: Desert

12: Defrocked

13: Lust

14: Coronation

15: Hallelujah

16: Inquisition

17: Visitation

18: Sin

19: Confession

20: Agony

21: Wrath

22: Baptism

23: Cross

24: Purification

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

To whom it may concern: I’m okay. I survived. So, it’s all good. Well, that’s probably an overstatement. But I am good. I don’t do what I used to do; I almost never even want to. That’s progress. I’m proud of that. This is starting to sound like a disclaimer, or a warning. Maybe it is. Please be forewarned: if you worry for the girl I was—the one you are about to meet—just know the woman I am is a fierce, mostly well-adjusted warrior, who cares for her well-being and yours, too—even though we don’t know each other.

I also care about my freedom. I take it very, very seriously. It’s what I live for. Constantly testing myself to take off another layer of my armor, another layer of shame and guilt, and be bold, be honest. Get naked. Fall. Cry. Hate. Love. I imagine it’s why I became an actress. Although, as wise as I think I might be, it took an outsider to explain, after reading this book, that I have always been an actress. There was no way I was going to be anything else—no matter how many careers I may have had before. She’s right. I’ve been acting my whole life. It’s how I got through it all.

After years of recklessness, I’m very careful about how I spend my time these days, who I share myself with. It might be hard to believe when you read about the girl I once was, but I’m coming up on twenty-five years of a loving partnership. She is my chosen family and the foundation for the work I do in all other areas of my life. When my partner and I have those occasional conversations about the blood and guts of our long-term commitment, I am still amazed how good it feels to risk it all in the name of honesty. I’m not interested in lying to her or to you. Pretending that I’m completely recovered from all of it. But I aim to be.

To be transparent, I’m not sober in the AA sense of the word, but I have chosen not to drink, as a way of making amends to myself. Mostly because, when I decided to become an actor at nearly thirty, I knew I had a lot of catching up to do. I learned very quickly in my first acting classes that I couldn’t fully access my emotions if I had consumed even a couple glasses of wine the night before. And so I stopped, because having an acting career that involved a full expression of my feelings trumped bold, rich, expensive Cabernet. My life improved once I decided to put my drama on stage and screen, instead of off.

Seven years ago, I decided that the next right step in my career and my healing—they have never been separate—would be to write and perform a solo show playing my deceased father. Like, literally, to put on a suit and tie, hair slicked, Dad’s English American accent operating, and to be him, no holds barred. My intention was to understand Dad more deeply. He had passed in 2005—five years before I embarked on the show. And I had long forgiven him for the things he did that you’ll soon read, so the hard part was over.

For many reasons, I do not believe telling the truth about Dad’s secrets is blasphemy, betrayal, unkind, or disrespectful. I don’t judge him. And there is much to learn from history. So, I took on his shame, his guilt, his poor decisions, his charm, and his goodness in front of a live audience. Daughter into father, transformed, I was him. I wasn’t acting Dad. I really felt I became him. In so doing, I finally understood him, his anger, his pain, his darkness, his love. The experience was a healing salve for my relationship with him. It was also one of the scariest things I have done, and that was before some of my siblings began sending e-mails. They said I was wrong, heartless, careless, thoughtless, and generally a bad person for telling the truth in a public forum. How dare I? And the fact that my tagline for the show was sardonic and funny proved their point.

There can be problems when you insist on telling the truth in a gigantic family that was raised in a culture of secrecy. I imagine that’s probably true even in small families. The challenge to tell it like it is can be overwhelming, as if you were swimming the English Channel with weights on your ankles. You might drown or you might find a strength you didn’t know you had. You might give up your people pleasing, disrobe from the keep-the-peace coat of armor you’ve spent much of your life wearing. You might come to terms with the fact that everyone in your family has their own wounds, their own version of the story, and their own sense of right and wrong.

I decided not to do polling about what should or shouldn’t be included in this book. To me there is no shame in telling the truth, but ironically, I think shame is usually the reason people don’t. Why do we keep secrets? Who are we protecting? And why? I find the whole truth invaluable. Worth the risk. Why would I want to pretend my father was just this holy man without telling the whole story? For me, his amazing life is a wealth of opportunity for teaching moments. There’s much to learn from him, and I’m interested in that journey. Not protecting his false image. Or mine.

I’ve had enough pretending; it consumed my childhood. Adults have asked me to keep their secrets since well before I was ten. I’m done. Not out of revenge, but out of a deep-seated belief that it’s the secret that causes the pain, the disease, the bondage, more so than the thing you are keeping secret. Maybe it’s true that the world will judge me, and Dad, label us sinners, horrible people, from a disgraceful family of so-called Catholics. It’s highly possible. But I say better that than to live a half truth, buried in secrets.

My third-to-last therapist used to say, “Tina, tell your family that you are not changing any of the names in order to protect the innocent.” She was a very progressive woman who knew that we are only as sick as our secrets—there’s never been a truer cliché, as far as I’m concerned. That said, I have changed names and descriptions of people and places, because I’ve come far enough to know that there’s only one voice to listen to when it comes to secrets and lies and telling your side of the story: your own.

So everything you are about to read is my truth. Well, to be clear, my younger self’s truth. I decided to write this story in the first person, sans the older, therapized me who might have been tempted to overanalyze, explain, justify, or hold your hand through this period of my life. More than anything, I didn’t want to mess with the purity of her experience. She—younger me—never felt safe to tell anyone what was going on. So this decision to let her lead was simply me wanting to stay out of her way. And honor her. I didn’t want to inaccur

ately portray her feelings and actions by planting my adult self between you and her. This is her story. So, I don’t claim to speak for anyone else’s experience. I know there are as many different stories and interpretations as there are human beings. I am one. And this is mine. And only mine. Take what you like and leave the rest. But when you are done, I hope you will come back to one thought that I really want you to remember: I’m happy. I’m good. Really.

1

Congregation

Even though she’s married and doesn’t live here anymore, my big sister Frances climbs the creaky stairs to the girls’ floor practically singing, “Tina, you’re dead.” Ever since I was a kid Frances has seemed to enjoy tormenting me. Once she woke me from a sound sleep by holding smelling salts under my nose, and when I was eleven she kicked my leg repeatedly while I read the four questions at our paschal meal. The only thing stranger than my not wanting to get Frances in trouble for torturing me over bitter herbs and haroseth is the fact that my devoutly Catholic family even celebrates Passover. Dad insists on observing everything involving Jesus.

The polished veneer of Frances’s burgundy gown and cropped velvet blazer can’t smooth out the bite in her attitude as she warns, “Dad’s asking where the hell you are.”

“Why me? Magdalene and Rebecca aren’t ready, either.”

Her laughter is acid. “Well, he hates you.”

I push into the steamy girls’ bathroom with a sudden stomachache, wishing she wasn’t right. He does seem to hate me.

“Please shut the door,” sweet Rebecca says from the shower.

While rolling my long hair in hot curlers, I kick the warped door shut. “You better hurry up, Dad’s pissed that we’re late,” I say to Rebecca.

The door swings back open, and Kate pops her head in. “Hey, Tina, do you have a hair ribbon I can borrow?”

“I don’t wear them anymore, I’m not into preppy.”

“There’s nothing wrong with preppy,” she insists, looking as pretty and conservative as a Kennedy.

Magdalene rushes in, grabs Kate’s wineglass. Chardonnay sloshes up the side as she eagerly tilts it toward her lips.

“Would someone PLEASE shut the darn door? It’s freezing,” Rebecca begs.

Magdalene peers through my panty hose. “Are those my lace underwear?”

She bumps me, pushing for center stage in our toothpaste-sprayed mirror.

“Give me a break, I wouldn’t touch your disgusting underwear.”

“I swear to God, those better not be mine!”

I give Magdalene the finger and walk out. Even though I admire her, we’ve always been competitive, probably since we are the two most athletic girls in our family. After sharing a bathroom with seven sisters for most of my eighteen years, it should be easier now that the last of us is in college. But having so many back home for the holidays reminds me how sick and tired I am of sharing—except when I don’t have clean underwear.

Careful not to smudge my freshly painted fingernails, I throw on a nightie, walk down the creaky steps, and slip along the dark-paneled second-floor hallway, past the boys’ bedrooms and the second-floor bathroom. The sounds of Christmas Eve at 5 East Irving Street rise up from the first floor: a blender swirling, the gurgle of baby talk from my nephews and nieces, the hard laughter of my five brothers, all coated by Johnny Mathis’s falsetto.

The heavy mahogany door to my parents’ room is open as I approach. A pile of unwrapped gifts and thirteen empty stockings are strewn across the floor.

“Is that one of my lovely daughters?” Mom calls out, her face lighting up as she sees me. “Ahhh, there’s my baby . . . just in time to help your mother with this.” Mom nods at the diamond and emerald necklace next to her on the bed. I kiss her soft cheek and breathe in the familiar smell of perfume and hair spray.

She is shaving a corn from her pinky toe with a straight razor blade. I glance at her purple ankles and calves—raw and veiny—and a lump forms in my throat.

“May I borrow a nail clipper?” I ask, tamping down my emotion.

“Sure, sweetie, in my side drawer.” She gestures to the cluttered bedside table that is spilling over with ripped coupons, a spool of thread, Scotch tape, and Christmas bows, spread among her rosary beads, a worn Bible, and a can of diet soda.

Mom moans as she sticks a Dr. Scholl’s corn pad between her toes and begins repositioning her two-hundred-plus pounds in order to get her feet into the support stockings, which are the thickness and color of an Ace bandage. She yelps as she pulls the hose over the four inches of redness between her ankle and calf, then pushes herself off the sagging bed. With a half bend, she tugs the hose over her wrestler-size thigh and attaches it to her white garter.

Dad flies into the room, holding an empty ice tray.

“What the bloody hell is taking so long?!”

I flinch at the vicious clip of his British accent and without thinking I’m standing in front of Mom—my sweaty hands fiddling with her necklace, my mouth dry.

“What do you need?” Mom asks kindly, stepping out from behind me.

Dad’s clean-shaven face is flushed with rage as he scans the mound of unwrapped presents. A dish towel, stained pink from the whiskey sours he’s been blending, is thrown over the shoulder of his ruby smoking jacket.

“What do I need? What do I need?! Well, for starters, I need someone to fill up the bloody ice trays around here! How the hell am I supposed to make sours for forty people with no ice?” he says, waving the tray in front of Mom’s soft blue eyes.

“Dear, the boys picked up bags of ice. I’m sure they put them in the basement freezer.”

“I don’t damn well care about bags of ice, what I care about is common courtesy!” His moist face turns toward mine, his large nose close enough for me to see his pores. “When you finish using a goddamn ice tray, fill it up!” he yells.

“Dad, I’ll go get the ice,” I blurt defensively.

He steps closer. I jerk away, expecting a slap, but am hit only by his cold, hateful stare. Dad only slapped me across the face once. I was eleven, in the kitchen with Mom, when he began to verbally attack her.

“Leave her the hell alone!” I yelled, as if I were David standing up to Goliath.

Too bad I didn’t have a sword. Now, Dad expresses his anger silently, those small green eyes oozing disdain at me, and his narrow lips turn down in disgust at my curlers, stockinged feet, and general lack of readiness.

“GET THE HELL OUT OF MY ROOM! You’re late! You girls will be late to your own funeral!”

It’s no secret that if it were up to Dad, he would have had thirteen sons and zero daughters. He was hoping to have at least enough boys to name after the twelve apostles. Sounds funny, but it’s no joke.

I stare down at the clean crease of his tuxedo pants, at the shine on his long black dress shoes, at the pale carpet.

“I just need to help Mom with her necklace,” I murmur defiantly, giving him my backside, refusing to leave.

Mom reaches for the flowy peach gown that hangs atop her closet door; her white slip rises, revealing her mounds of dimpled flesh.

“Oh, for God’s sake, woman, you really need to lose some of that weight,” Dad says, his nostrils flaring as a look of repulsion sweeps over his face. Mom drops her head like an abused stray. I want to strangle him, but before I do anything he swivels toward the door and kicks a pile of gifts: flannel pajamas fly out of a white box; bags of stocking stuffers spill; a record album sails across the room and into Mom’s bare, raw leg. A whimper escapes her lips.

“How many bloody gifts does this family need? There are children starving all over this world!” And with that, he marches out.

“John, I’ll be right down,” she calls meekly, swallowing the humiliation like a communion wafer.

We silently check for broken skin, only finding a small indentation in the center of her shin. I look away. Dad’s immaculate bedside table is set like a church altar: satin runner, wooden rosary beads, a pocket

Bible, Italian lire lying in a fine china dish engraved with an image of St. Peter’s Basilica, prayer cards stacked as neat as a casino deck.

“Tina, zip me up, please,” Mom gently commands while running rose lipstick over her mouth.

“Sure,” I whisper.

“I must be shrinking or you’re still growing. Heavens, I used to be five foot six,” she muses.

I look at us standing in the mirror. At sixty, she must be shrinking, because I’m definitely five foot six—same as I’ve been since I was twelve, and I’m probably not going to have another growth spurt. Not even my University of Maryland basketball coach can scream more height out of me. I drape the jewels across her throat, staring at our reflections. My body is like Dad’s—narrow hips, long legs—but my face is Mom’s—almond-shaped blue eyes, strong thin nose, delicate lips, and pale skin.

“Now, hurry and get dressed, sweetie. Let’s not upset your father any more.”

* * *

In the corner of the foyer, a ten-foot Douglas fir dazzles with colored lights; candy canes; my favorite ornament that I always hang: an elf holding a basketball; and perfect crisp gingham bows that preppy Kate pressed and tied before draping the tinsel one strand at a time. A sea of presents swells out from under its branches—six feet deep and four feet high. With the noise rising, my body tightens as if bracing for a cresting storm wave.

I inhale the pine, perfume and cologne, roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, and Dad’s infamous Cabernet-soaked gravy; slowly, the tight spot in the middle of my chest eases.

“Farrah Fawcett, watch out! The baby of this family is all grown up!” My brother-in-law Chip whistles as I descend the staircase, the last to arrive at our Christmas Eve celebration.

“Nice of you to join us,” my brother Simon says dryly, then sucks on his whiskey sour and eyes my dress over the lip of his crystal glass.

“Shut up,” I murmur without meeting his gaze.

“Excuse me, what did you say?” He feigns aggression.

Hiding Out

Hiding Out