- Home

- Tina Alexis Allen

Hiding Out Page 2

Hiding Out Read online

Page 2

Simon’s wife, Becky, rushes out of the packed living room toward us.

“Tina, don’t you think that dress is more appropriate for New Year’s Eve than Christmas Eve?” She gives me a tight smile.

It is as noisy as a henhouse where the rest of my family has gathered around the hors d’oeuvres in the living room. Not even the wall-to-wall carpet can mute the sound.

Kneeling in front of the decommissioned fireplace that houses the Nativity scene, Rebecca gently points out the various players to a few of the children. Above them hang portraits of Mom and Dad wearing their Knights of the Holy Sepulchre robes embossed with the crusader cross on their hearts. My parents are so devoted to the Catholic Church that they have been knighted—Sir John and Lady Anne Worthington—by Pope Pius XII.

Hanging between the paintings is a three-foot crucifix—a reminder that your troubles are irrelevant in the grand scheme of all Jesus endured.

“Hey, kid,” my sister Margaret calls while blowing her cigarette smoke toward the high ceiling.

Then a swarm of beautifully dressed creatures converges on me, tossing comments like rice at a wedding: “Oh, you look pretty, Tina.” “Neat dress!” “Hey, baby sister.” “It’s about time.” “Diego, look at her figure: holy moly, I should play basketball!” “How’s the season going, Tina?” “You dating anyone?” “Hey, hot dog, how’s the jump shot?” “Go Terrapins!”

“Hi . . . Thanks . . . Hi . . . Good . . . I like your dress, too . . . Shut up . . . The season’s going great . . . No, not dating anyone,” I fire back at them—mostly lies. Keeping secrets in a big family is easier than one might think, because with so many people, there’s no chance for a real discussion. It’s all one big constant interruption. When questions get too personal, I just turn my head to another conversation.

Margaret’s husband, Diego, puts his thin arm around me.

“You look almost as good as I do tonight,” he teases.

Even I can see that his fitted black suit and movie star looks could cause girls to throw their panties. Rowdy laughter and high fives erupt from the corner where three of my brothers in their boxy suits—Luke, Matthew, and Paul—are shaking their heads in our direction.

“Where’d you get that suit, fag?” Luke japes.

“You expecting a flood on Christmas Eve?” Matthew points at Diego’s tapered pant leg.

“Yeah, I am,” Diego banters.

“Okay, but Sammy Davis Jr. wants his suit back, faggot,” Paul cracks.

Dad staggers up to Diego and me, but I refuse to acknowledge him.

“Christine, you finally decided to join us,” my father slurs, handing me a whiskey sour. His black bow tie pinches the blotchy skin of his neck.

“I was late because I had basketball practice,” I answer brusquely, sipping my drink.

Dad nods approvingly at Diego’s suit. “Young man, there are more sours in the blender, don’t stand there with an empty glass.”

“Tina, you want a refill?”

“No, I’m good—”

“Her name is Christine! I never understand why you people must bastardize a saint’s name.” Dad squeezes the back of Diego’s neck, sending him on his way.

Gazing up at the crucifix, Dad reaches inside his velvet jacket, resting his hand on his heart as tears form in his eyes.

“Christine, please . . . take a moment to see . . . look there.” He points his index finger toward Jesus on the cross, his massive ruby ring distracting my glance.

“How dare we complain?” my father says softly, wiping a tear away. He assesses the crèche. Each year Dad gets down on his knees to set up the Nativity scene. For these hours, he is a stranger to me, acting gentle with his wooden flock, but it’s too short a time for me to let my guard down with him or expect his love will shine my way. Dad’s main squeeze seems to be Jesus—whether the baby in the manger or Jesus the man, who’s plastered on the cross throughout our house in every art form: statues, sculptures, prints, and paintings. Dad never gets wrapped up in our birthdays the way he does Christ’s. In fact, he doesn’t know our birthdays, only our feast days—the birthdays of the saints we are named after. The closest he ever gets to fatherly behavior is when he lays out straw, props up camels, and steadies the wise men bearing gifts. His final ritual for setting up the Nativity is kissing baby Jesus and then covering the little guy with one of his crisp white handkerchiefs, to remain in place until Christmas Eve.

“Christine, our most gracious and gentle Savior was born and then died for your sins. This . . . you must never forget.”

I look for an exit strategy and gulp my drink. An electrifying freeze spreads through my brain just as Mom enters the room carrying a plate of stuffed mushrooms. She transforms into a beauty on Christmas Eve, a rare occasion when she takes a little time for herself, wearing makeup, jewels, and a gown from Lane Bryant. My siblings swarm her, and she beams, as happy as she’s been all year, in the midst of her children.

“Mom, do you need help?”

“Sit, Mom, you have to try Gloria’s spinach dip.”

“What can I do?”

“You look lovely, Mom.”

“Mom, why don’t you put your feet up and let me take over?”

She drinks in all the attention. Dad watches, polishing off his sour.

“Your mother is a saint,” he says with envy, knowing none of us love him half as much as we love her. He then takes a plastic bottle of holy water from the mantel.

“Shall we bless the tree? Children! Mother!” He waves his large hands as if leading one of his pilgrimages, and there’s a rush of velvet, satin, chiffon, and fine wool into the foyer. Someone shuts off the music, and the excited and tipsy adults surround the magnificent tree, the little ones pushing to the front, practically eye to eye with the mountain of gifts. The lights are dimmed as Dad begins to sing.

“‘O come, O come, Emmanuel, and ransom captive Israel that mourns in lonely exile here.’” Dad’s beautiful tenor—perfected during years in a prestigious London boys’ choir—ignites a longing within me. Perhaps I want to bask in some of the attention he gives Christ.

Helen, the oldest girl and my godmother, wraps her arm around my waist, reminding me how lucky I am to have big sisters. The boys are huddled together, belting through their chuckles. Mom croons next to Dad, hands folded, eyes glistening as she gazes at her brood.

I feel a powerful rush of love and pride in my family; it takes my breath away. I wish this moment could last and utter a prayer that Dad’s temper will remain softened by whiskey. As we continue caroling, he douses the tree with the holy water, then passes the bottle to Mom to hold as he picks up a linen scroll.

“Family, we have received a special apostolic blessing from the Holy Father,” Dad announces, unrolling the paper. He reads slowly, exaggerating his accent: “His Holiness, John Paul II, cordially imparts his apostolic blessing to the Worthington family and invokes an abundance of divine grace.”

The singing starts again, and I finally find my voice when the gang roars, “Five golden rings!” in a laughter-filled rendition of “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” Then Dad herds his Trapp Family Singers back into the living room to bless the manger.

“Owww!” I cry out, feeling a sharp pinch under my arm.

Dad glares at me; Simon snickers. I’d like to shove him into the tree, let the pine needles do my dirty work, but repress my fury instead. Dad makes a grand sign of the cross over the Nativity and the family follows. I join the ritual out of obligation. Dad reads from a small black prayer book. “An angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, ‘Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: you will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.’”

Dad hands Mom the prayer book as he gets down on one knee, bowing his

head with great reverence and tenderly removing the handkerchief. Christ is born. He tucks the handkerchief inside his jacket, rises, and offers a final blessing: “In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Now, who wants a whiskey sour?!”

* * *

As soon as dinner is over, I stealthily slip away and into the front hall.

“Where the hell do you think you’re going?” Simon demands as I wrap a black cashmere scarf around my shoulders.

“Out,” I say, trying to act casual while searching for Mom’s car keys near the front door. He steps closer, his over six feet of height dominating me, even in my heels.

“Yeah, smart-ass, I figured that. Where? Midnight mass starts in a half hour. I’m sure Dad wouldn’t appreciate you leaving in the middle of dessert.”

There are a million things I could probably scream at him right now, but there’s no bridge from the shoreline of my feelings to the depths of the words.

“I need to get Mom some stocking stuffers at the drugstore, okay?” I lie effortlessly, hoping he won’t be a dick and draw attention to my exit.

“I’ll save a seat for you at mass,” he says, softening, and heads into the loud dining room.

Grabbing the Chevy key chain from next to a commemorative tiara of Pope John Paul, I slip out the front door. Sneaking off the wraparound porch, happily away from that game of secrets I play when around my family, I want to giggle, to dance and swing my arms like a schoolgirl. Despite the frosty night blowing through my dress I glide down the front steps. The massive elm trees dusted with an early Maryland snowfall spread their arms wide, as if celebrating with me.

I breathe easily into the night and cross the frozen lawn to the end of our long driveway. Thrilled to drive—soul music blasting—to my girlfriend Nic’s house for a quick Christmas make-out under the mistletoe among her gay friends, who are too old to worry about sneaking out.

“God damn it,” I yell. Three people have parked behind my getaway car.

I peer through icy windows for keys left in the ignition. Nothing. Inside Simon’s Honda, I spot my favorite basketball—an expensive leather game ball I stole last year from my high school equipment room—on the vinyl seat. The asshole is still taking my shit without asking.

Toes numb, my slight buzz now sour, I climb back onto the porch and peer through the bay window. In the dining room, the oval teak table is packed elbow to elbow. A separate kids’ table is elegantly set for the overflow. Fat silver candelabras cast a glow over the china and burgundy wine. The ocher mission jar—a staple in the center of the table for as long as I can recall—has been moved to the end of the buffet tonight. Still, Dad expects us to drop at least a penny a day into it so that the kids from the Home of Peace orphanage in Jerusalem can have food on their table and get a decent first communion outfit.

My chair is taken by my eight-year-old niece, who is singing for two of my brothers. At the far end of the dining room table, Dad shakes his head—a look of disgust covers his ruddy face, nostrils wide in a huff. Nose pressed against the frosted front window, I watch Dad’s rage build.

He slams his hand down, turning a silver breadbasket upside down. French rolls go flying. The chaos halts. Grown-ups become childlike, with wide eyes and tight mouths, as Mom bows her head. Dad’s muffled yelling reaches the porch as he stands up and throws down his cloth napkin. Sheepish faces watch him leave the room as he screams, waving his hands in a rage.

I wish he’d leave for Rome right now, instead of tomorrow.

2

Blessings

When it comes to older women, I’m a barnacle. The slightest bit of intimacy, and I’m no longer eighteen, I’m struck, stuck, needing to be fed like a hungry toddler. Even Coach Norris noticed something between me and Shawn—one of the assistant coaches at Bergen State—our opponent tonight. Coach hovered around our quick postgame conversation as the rest of my teammates boarded the Greyhound for our three-hour ride back to campus.

“Tina!” Coach Norris calls, standing at the door of the bus, a slight smirk across her handsome face.

I climb onto the bus and find an empty seat in the front—normally, the quieter section where those players who want to study sit. The back is noisy; a boom box plays Chaka Khan. The bus grinds away from the small college gymnasium.

“You okay?” Norris whispers, leaning on the upholstered seat next to me, holding a stack of small white envelopes. Unintentionally, I catch her eyes—they seem to be assuring me that whatever I say won’t be held against me. Just a secret between her and her freshman player.

“Yeah, I’m okay.” I act cool, pretending she didn’t just watch me flirting away with an opposing coach.

“You want to talk about it?” She smiles.

I fake a smile back, shaking my head, afraid that she might tell Nic—her friend, my girlfriend—whatever I say. No way I want to deal with that fallout. Keeping secrets is a second skin I wear, even with people I know are gay, like Coach Norris. She stares at me, probably hoping her authority will break my silence, but this is lightweight compared to most of the things I’ve hidden.

“Here you go.” She hands me an envelope with my per diem and walks down the aisle to pass out the rest. After a short distance on I-95, I see the golden arches of McDonald’s in the distance. Our husky driver exits the New Jersey turnpike, cruising around the off-ramp, toward our pit stop. Full with longing, I’m not hungry.

I remember the special Friday nights when Mom didn’t feel like cooking and broke the rules—good Catholics shouldn’t eat meat on Fridays—by feeding us McDonald’s when Dad was overseas, which was most of the time. We’d have to call ahead to have them specially prepare our order: twenty-six hamburgers—most of us got two—fourteen large french fries, plus apple pies and milk shakes. Only Mom would remain reverent, ordering a Filet-O-Fish. I always went along to pick up the food, so I didn’t get stuck with one of the french fry containers that had been ransacked. Being the youngest of thirteen makes you crafty, keeps you on your toes, and trains you to run like hell when you hear “DINNER!” so you can get a place in the front of the chow line.

My teammates pile off the bus as I feign serious involvement with my political science textbook. I stretch out across two seats and open the per diem envelope. A crisp ten-dollar bill seems puny compared to the spending money Dad would give us. Maybe to make up for his lousy childhood in London during World War I, which included rationing and air raids; a stepfather who beat him with a belt, according to Mom; or worse, being a bastard child. In 1920, Dad’s mother and her husband, Mr. Worthington, left London for Alberta, Canada, with their infant son, Ed, to find work. While working on a ranch, Dad’s mother had an affair with the horse trainer. Eventually, pregnant with his child, she left in disgrace back to England, her marriage to Mr. Worthington over. Dad was born in London, his mother pretending Mr. Worthington was the father, when, in fact, Dad’s father was secretly the horse trainer. When Dad was thirty, he tracked down Mr. Worthington and learned the truth: Worthington wasn’t his old man. And despite further attempts, he never found his father. Dad’s real last name—our real last name—will never be known.

Soon after Dad was born, his mother left him and his older brother with her mother, who had thirteen kids of her own, while she went cavorting around London. A few years later Dad’s mother retrieved her sons to live with her new husband, Mr. Hall, the stepfather who beat Dad frequently. Maybe that’s why Dad yells and screams so much.

In order to escape his stepfather’s fist, Dad lied about his age and joined the British Merchant Navy at sixteen. During World War II, while serving with the British Army in Palestine, Dad seriously considered joining the priesthood. On a brief leave, he was in Jerusalem at the same time as Anne Allen. She was a nurse in the American army on leave from Africa, visiting the Holy Land for the first time. She became our mother.

On Good Friday 1944, Dad, practically a scholar of Catholicism, offered to give Anne Allen a guided tour of the Stations

of the Cross. Not a romantic date, but it makes sense when you consider how much both of my parents adore Jesus. In the photo of them walking the cobblestone Via Dolorosa—the path that Christ took to his crucifixion—they are sporting their military uniforms. Dad looks beefier than the skinny man I’ve always known and a bit nerdy with his thick black glasses—blind as a bat even then; and Mom, big boned but not yet fat, looking kinda butch with her short hair, sturdy shoes, purposeful stride, and striking New England looks. Sometimes I wonder how long it took my father’s sharp tongue to wear down that strong woman, who proudly served her country and who stands even more erect than he does in the photo.

My mother has always been very patriotic, enlisting in World War II not because she has an aggressive bone in her body but because she felt it was her duty, since no one else in her family could. Her eyes get watery as quickly during “God Bless America” as they do when she talks about losing her father when she was nine or reminisces about Winnie, her sister, who at age twenty-seven died of tuberculosis, when Mom was just twenty-two. When Winnie was bedridden she wrote a poem to Mom: “Day after day bed-fast I lie, gazing lastingly at the sky. / How oft comes the sweet memory of my dear sister Anne and me. / At sunset, before the nightfall, to my dear Anne I would call, / come with me and watch by my side at the beautiful clouds as they ride.” Not Wordsworth or Tennyson, but full of undying, sweet, corny, sisterly love.

Sometimes I’m not sure if it’s Mom’s Depression-era upbringing as the youngest of five children, or all the loss, that makes her warm chubby face unable to mask the droop of sadness. Yet, melancholy as she often seems, I’ve only seen her cry once.

My nana—whom I never met—was a devout Catholic, kind and selfless like Mom, but looked as serious in photos as the lady in American Gothic. During the Great Depression, and despite the frigid New England winters, Nana Allen, a jobless widow, waited until her children got home from school to light the coal stove. They were so poor, the nuns at Mom’s Catholic school gave her an old uniform to wear. It must have felt good for Mom to be able to buy all of us brand-new school uniforms and saddle shoes every year. Mom talks much less about her dad, an Irish bar owner, who I’m pretty sure served himself a drink as often as he served his customers. Mom doesn’t remember a lot about him, since she was so young when he died, but she does recall that Nana used to say, “Little girls shouldn’t sit on their father’s lap.” Why would she say such a weird thing? I have always wondered if Grandpa Allen bothered Mom, or was Nana just warning her because of something that happened to Nana when she was a little girl?

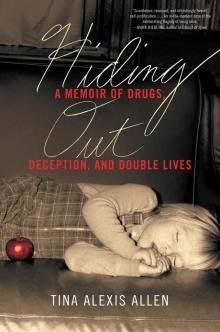

Hiding Out

Hiding Out